Workshop provides practical advice for translating research to society

Small business owners, entrepreneurs and academic researchers recently gathered at the University of Delaware’s Science, Technology and Advanced Research (STAR) Campus for a special workshop to learn ways to successfully compete for federal funding to move health science innovations from the lab to consumers.

Miguel Garcia-Diaz, UD vice president for research, scholarship and innovation, opened the program by sharing a conundrum found on many university campuses: Universities are at the core of innovation and faculty excel at making groundbreaking discoveries, but translating these breakthroughs to society doesn’t always happen. Sometimes this is because researchers don’t want to become entrepreneurs or business owners. Other times they struggle to find partners or funding to take their innovations to market.

At UD, changes are afoot to encourage the academic culture to embrace innovation and entrepreneurship. Last year, for example, UD was selected to receive funding from the National Science Foundation’s inaugural Accelerating Research Translation (ART) program, which is enabling the University to invest in more infrastructure for translating research into practice.

“We are really working hard to make this part of our DNA,” Garcia-Diaz said. “We understand that [research] translation is a team sport … and that translating does require public-private partnership.”

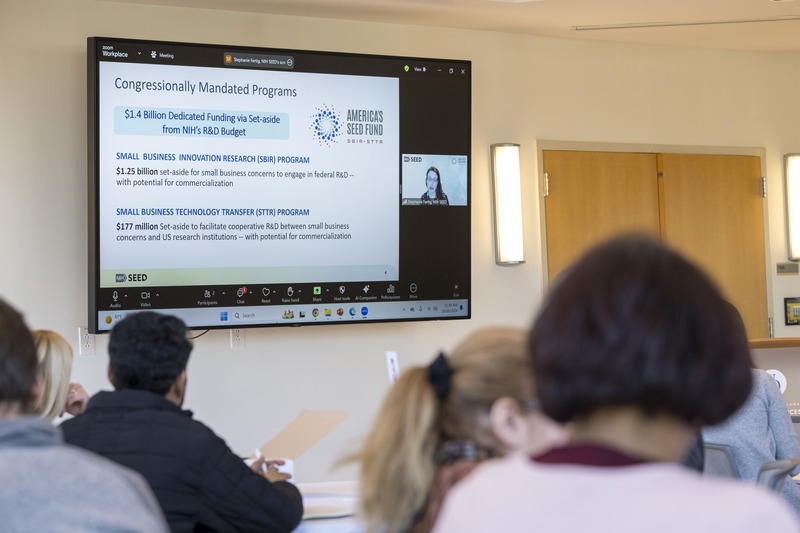

The event, hosted by the Institute for Engineering Driven Health, College of Health Sciences and Delaware Small Business Development Center, featured a virtual presentation by Stephanie Fertig, director of small business innovation programs at the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Over the past 20 years, the University’s NIH research expenditures have grown from about $8 million a year to almost $50 million. Meanwhile, the explosion in biomedical research is starting to yield more opportunities for translating research discoveries into practice where they can have a positive impact on people’s lives. Many UD faculty and researchers are at the forefront of this effort.

Getting these innovations into the hands of clinicians where they can benefit society often starts with de-risking technology. The Small Business Innovation Research (SBIR) and Small Business Technology Transfer (STTR) programs are federal grant programs that provide early-stage capital to help small businesses take these steps toward commercialization through seed funding. At NIH, these congressionally mandated set-aside programs provide more than $1.4 billion per year to small business concerns.

At the University of Delaware, changes are afoot to encourage the academic culture to embrace innovation and entrepreneurship. One example: small business owners, entrepreneurs and academic researchers recently gathered at the Science, Technology and Advanced Research (STAR) Campus for a special workshop to learn ways to successfully compete for federal funding to move health science innovations from the lab to consumers.

In her current role, Fertig oversees the NIH SBIR/STTR programs, and she previously managed the SBIR/STTR programs at the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke. A patent holder herself, she also co-chairs the entrepreneurial workforce development working group and seeks to foster a culture of innovation that is both inclusive and equitable.

Fertig suggested that those planning to submit for SBIR/STTR funding explore what the NIH has funded in the past to learn what the agency typically funds and what other peer companies exist in the space. She also hammered home the point that most proposals do not get funded on the first try.

“Only about 15-20% of submissions are funded; resubmission is just part of the process,” she said.

Fertig offered these top tips for submitting SBIR/STTR proposals:

- Build a team because “no one person has all the experience and knowledge needed.”

- Volunteer to become a peer reviewer to get better at submitting this type of proposal. “Nothing will get you there faster.”

- Have someone read your proposal prior to submission. Fertig recommends asking peers who challenge your way of thinking, someone who will help you see and correct gaps you might not otherwise recognize yourself.

- Submit early – days early, not hours.

- Most importantly: Talk to your program officer at least a month ahead of submission — the earlier the better.

She also introduced two programs to help innovators prepare for the SBIR/STTR proposal process: C3i program – Accelerator is a pre-application SBIR program that provides up to 12 months of technical development and business support for NIH-funded researchers interested in pursuing SBIR/STTR funding, while the Small Business Transition Grant for New Entrepreneurs aims to support career development and training opportunities for new entrepreneurs.

Stephanie Fertig, director of small business innovation programs at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), delivered a virtual presentation and shared best practices when competing for federal funding opportunities.

Fostering connections

Following Fertig’s presentation, several members of UD’s inventor community in various stages of research translation spoke about their individual experiences.

There was Michele Lobo, associate professor of physical therapy and of fashion and apparel studies, who specializes in smart garment and functional fashion for people with disabilities. Lobo’s route to successfully securing Phase I SBIR funding through the Nursing Institute for Healthcare Design was circuitous.

The winding journey to develop her platform technology for identifying developmental delays in young children using smart home monitors started, she said, ‘from me trying to get an NIH R01 grant to exploring a clinical trial through the Institute for Education Sciences” and grew to collaborations with the local health system, and introductions to small business owners that would ultimately help lead the way.

“We started with a different funding plan and got close, but didn’t quite make the cut … but the small business was a good fit for me, so we kept collaborating,” said Lobo, who serves as co-director of innovation in UD’s College of Health Sciences. “Then, a year later, NIH had money left at the end of the fiscal year and came back to us.”

Today, with SBIR Phase I funding, Lobo and her small business colleagues are working to collect data using computer vision and artificial intelligence approaches with the potential to help clinicians make more informed evaluations during well-baby visits about whether a child has developmental delays.

Neil Butler, co-founder of the synthetic biology company Nitro Biosciences, which he developed with UD engineer Aditya Kunjapur, offered his perspective on research translation as a graduate student and postdoctoral researcher.

A robust Q&A during the event enabled participants to gain insight and make connections.

Understanding where this discovery might fit in the marketplace, however, required work. Butler took advantage of Horn Entrepreneurship’s NSF I-Corps Sites program, Delaware Biotechnology Institute’s Entrepreneurial Proof-of-Concept program, and the NIH small business technology transfer (STTR) program. He encouraged others in the audience to do the same.

“Broaden your horizons and understand the ecosystem better,” Butler said.

Getting started can be daunting. One small business owner raised his hand and asked how, exactly, to make connections.

“We want to partner with you. We have the expertise, the equipment and desire to do innovative partnership and projects,” said Jill Higginson, inaugural director of the Institute for Engineering Driven Health (IEDH) and co-director of the NSF ART program at UD. “Our mission is to develop and translate medical technologies to improve human health, to meet the faculty where they are — and you where you are — to help prep for different kinds of commercialization pathways.”

At IEDH, this has included an emphasis on translation of functional prototypes for experimental validation studies related to population health. This includes K9 Kevlar for canine ballistics protection, pressure sensor-equipped garments for the prevention of sudden infant death syndrome, even customized protective gear for athletes recovering from injuries.

A great first step for new entrepreneurs or small business owners looking to engage with the University is to visit UD’s Innovation Gateway, according to Tracy Shickel, vice president of corporate engagement at UD.

“As we continue to transform the culture here at the University, making connections within our different ecosystems is very important. Fill out the form and indicate your interests and let UD do the matchmaking,” Shickel said.

Article by Karen Roberts | Photos by Kathy F. Atkinson (featured on UDaily, 11/13/2024)